The forgotten 8-Bit Hero:

Sega Master System Shaped a Generation

In the mid-1980s, the video game industry was still reeling from its first great crash. The early years of home gaming — dominated by Atari, Mattel, and Coleco — had ended in oversaturation and consumer fatigue. Many believed that home consoles had peaked. Yet across the Pacific, Japan’s electronics companies saw a different future: a new generation of consoles that combined arcade-quality graphics with affordable home entertainment. Among these companies was Sega, a firm already famous for its coin-operated arcade machines. Its response to the changing times would be the Sega Master System, a console that never quite won the global race, but which left an indelible mark on gaming history.

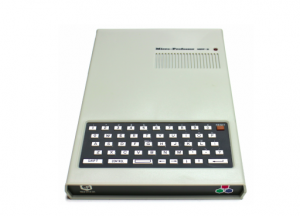

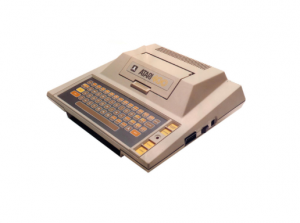

Sega’s console lineage began with the SG-1000, released in Japan in 1983 — the very same day Nintendo launched its Famicom. The SG-1000 and its successor, the SG-1000 Mark II, were promising but modest machines. Sega’s engineers, however, were determined to leap ahead technologically. In 1985, they unveiled the Sega Mark III, a sleek new system powered by an 8-bit Zilog Z80A processor running at 3.58 MHz. It offered far superior graphics and sound compared to its predecessors, and it was fully backward compatible with SG-1000 games. The Mark III impressed the Japanese market with its colour palette of 64 shades and a resolution of up to 256×192 pixels — features that put it technically on par, if not above, the Nintendo Famicom.

Sega Master System in operation at the I love 8-bit® -exhibition in Finland 2024.

When Sega prepared to enter the Western market, the company rebranded the Mark III as the Sega Master System. The new name, and the new design, reflected a clear intent to appeal to consumers outside Japan — particularly in North America and Europe. The system launched in Japan in October 1985, in North America in 1986, and in Europe and other territories in 1987. Its hardware was essentially identical to the Mark III, but it featured a more futuristic black-and-red casing and a redesigned cartridge format. Sega also introduced a smaller “Sega Card” format — thin credit card-sized game cartridges that could hold up to 32 kilobytes of data.

Technically, the Master System was an impressive piece of engineering for its time. Its graphics processor could display more colours and more on-screen sprites than the NES, and its sound chip — the Texas Instruments SN76489A — produced richer tones than Nintendo’s simpler audio hardware. Optional accessories expanded its capabilities further: a light gun called the Light Phaser and 3D glasses that worked surprisingly well with compatible titles such as Space Harrier 3D and Maze Hunter 3D. These technical achievements gave Sega a powerful marketing message: the Master System was the most advanced 8-bit console in the world.

However, technology alone could not guarantee success. When Sega entered the American market, Nintendo had already transformed the industry with its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). The NES had not only revived gaming after the crash, but also built a vast ecosystem of exclusive software and loyal developers. Nintendo’s licensing policies effectively prevented most third-party companies from producing games for rival consoles. Sega thus found itself fighting with one arm tied behind its back: even though the Master System could outperform the NES on paper, it struggled to compete with Nintendo’s game library and market dominance.

To make matters worse, Sega’s American distributor, Tonka, lacked experience in the video game industry. Marketing was inconsistent, and distribution was limited. The Master System’s packaging and advertising often failed to capture the imagination of children in the way Nintendo’s did. As a result, in North America, the console never sold more than a few million units. Estimates suggest that by the early 1990s, total Master System sales in the U.S. were around 2 million, compared to more than 30 million NES units.

Yet the story of the Sega Master System was far from a failure — it simply unfolded differently depending on where one looked. In Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom, France, and Spain, Sega’s console found a welcoming audience. European players were less bound by Nintendo’s exclusivity agreements, and Sega partnered with local distributors such as Virgin Mastertronic, who marketed the console aggressively and effectively. The Master System became a household name across Europe, where it often outsold the NES. Its sharp visuals and fast-paced games appealed to European tastes, and its lower price compared to the later Mega Drive made it an enduring success well into the 1990s.

In Brazil, the Master System became a phenomenon. Through a partnership with TecToy, Sega localized the console, translated games into Portuguese, and even created original Brazilian exclusives. The Master System’s popularity in Brazil was so great that production continued there for decades — long after it had disappeared elsewhere. Even today, TecToy continues to release updated versions of the system, making the Master System arguably the most long-lived 8-bit console in history.

Critically, the Master System was admired for its craftsmanship and arcade-style design. Reviewers in the 1980s praised the console’s smooth scrolling graphics, clean audio, and futuristic styling. Its build quality was high, and its controllers — small rectangular pads with a simple D-pad and two buttons — were responsive and comfortable. The built-in game Hang-On or Snail Maze (depending on the model) ensured that every owner had something to play immediately. Sega also capitalized on its arcade heritage, bringing home versions of its coin-op hits such as Space Harrier, Out Run, and Shinobi. These titles showcased the Master System’s strengths and gave it a distinctive identity: fast, colourful, and slightly more mature than Nintendo’s cheerful world of plumbers and princesses.

Still, the console had its weaknesses. The game library, while respectable, never matched the sheer volume and variety of the NES. Many developers were tied to Nintendo contracts and could not release titles for Sega’s system. The Master System’s sound chip, while technically superior in some respects, lacked the warmth and musicality that characterized many NES soundtracks. In North America and Japan, where brand loyalty to Nintendo was strong, the Master System was often seen as the “other console” — technically impressive but lacking in magic.

Nevertheless, for players who owned one, the Master System delivered memorable experiences. Titles such as Alex Kidd in Miracle World, Phantasy Star, Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap, and R-Type became beloved classics. Phantasy Star in particular stood out as one of the most advanced role-playing games of its era, featuring 3D dungeons and a complex story long before such features were common. These games hinted at the creativity and ambition that would later define Sega’s 16-bit era.

In the end of 1980’s, Sega introduced the Mega Drive (known as the Genesis in North America), the Master System gradually faded from the spotlight. In Japan and the United States, it was discontinued by 1991, but in Europe and South America it persisted much longer. The Master System II, a smaller and cheaper redesign released in 1990, kept the brand alive for several more years. By the end of its life, global sales were estimated at over 13 million units — modest compared to Nintendo’s dominance, but enough to establish Sega as a formidable player in the console wars to come.

Looking back, the Sega Master System occupies a fascinating space in gaming history. It was both a success and a failure — a commercial underdog in some markets, a cultural icon in others. It proved that technology and design alone were not enough to win a console war; distribution, licensing, and software mattered just as much. Yet it also laid the foundation for Sega’s later triumphs. The Master System’s technical sophistication and arcade spirit foreshadowed the style and energy that would define the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis, and its influence can still be felt in Sega’s modern brand identity.

Today, the Master System is remembered with affection by collectors and retro-gaming enthusiasts. Its sharp, clean graphics, bright colour palette, and distinctive game library stand as a testament to an era when consoles were simpler but full of character. It reminds us that even the “second place” machines of history can have stories worth telling — stories of innovation, resilience, and regional success.

The Sega Master System may not have conquered the world, but in its own way, it changed it. It taught Sega how to compete globally, it brought joy to millions outside Japan and America, and it laid the groundwork for one of the most dynamic rivalries in entertainment history: Sega versus Nintendo. In that sense, its legacy is larger than its sales figures. It was the console that dared to challenge a giant — and in doing so, ensured that video gaming would never again be a one-company world.